Illinois is finally joining the 41+ other states and territories which have switched to looking at both parents’ incomes in determining child support. This is a major change in how child support is computed, and may change what we see as results in the amount of child support awarded in our cases. This article will explain how the new guidelines will work, and why they are going to help make our lives as divorce practitioners easier. I will not be even trying to address all the details and intricacies of the new statute, there is no substitute for actually reading the text of the statute.

The income shares legislation was passed as HB3982, and enacted as P.A. 99-764. This law will become effective July 1, 2017. In addition, there is planned a trailer bill to correct some errors and make some changes to the statute, which is hoped to be in place by the time the statute itself becomes effective in July 2017.

First, let me note that the change in the computation method, even if the result under the new method would be substantially lower or higher, will not in and of itself be grounds for a modification of child support. Section 510 will specifically provide:

“The court may grant a petition for modification that seeks to apply the changes made to subsection (a) of Section 505 by this amendatory Act of the 99th General Assembly to an order entered before the effective date of this amendatory Act of the 99th General Assembly only upon a finding of a substantial change in circumstances that warrants application of the changes. The enactment of this amendatory Act of the 99th General Assembly itself does not constitute a substantial change in circumstances warranting a modification.” (emphasis added)

Second, the actual computation of the amount of child support cannot be found in the statute. As stated in section 505(a)(1):

“The Department of Healthcare and Family Services shall adopt rules establishing child support guidelines which include worksheets to aid in the calculation of the child support award and a table that reflects the percentage of combined net income that parents living in the same household in this State ordinarily spend on their children.”

The statute does not really define what these new guidelines will be or how these new child support guidelines will be applied. Instead, the statute delegates the responsibility for establishing the guidelines and the tables to the Department. The planned trailer bill will provide more specifics on the computation method and formula, but the actual Schedule of Child Support Obligations will still be established by the Department.

The computations themselves cannot be done until the Department issues rules, including a “Schedule of Basic Child Support Obligations” (Schedule) which will hopefully be done shortly. [In preparation for the legislation, the state did have such a table prepared in 2012, which will need to be updated]. Here’s how we expect the new child support guidelines will work:

- Determine each party’s net income. We start with the definition of income, which continues to be all income from all sources, as under previous law [there are some specified exceptions for SNAP, TANF and SSI and other government benefits which basically incorporate prior case law]. Also note the statute specifically provides: “Spousal support or spousal maintenance received pursuant to a court order in the pending proceedings or any other proceedings must be included in the recipient’s gross income for purposes of calculating the parent’s child support obligation.”

- Next, the statute allows two methods for computing deductions for taxes from gross income to arrive at net income:

a. Standardized tax amount; or

b. Individualized tax amount.

The standardized tax amount will be based on utilizing the standard deduction, rather than itemized deductions which may exist in a particular instance. It is anticipated in the statute that the Department will publish a table reflecting the application of the standard deduction to the gross income numbers to determine net income. Many of us remember and still use the ‘DuCanto’ tax tables published each year by the law firm of Schiller, DuCanto & Fleck (SDF). The Department published tax table will likely be similar, although not as complex and complete, as the SDF version.

The standardized tax amount will be based on the support obligee, not the obligor, receiving the dependency exemptions for the children (the statute still refers to “custodial parent”, a term now not part of our statutory lexicon, and will be corrected in the trailer bill). It will also be based on the rate as a Single taxpayer, with one personal exemption. In addition to Federal and State taxes, the computation of net income will allow the deduction of Social Security and Medicaid taxes calculated at the Federal Insurance Contributions Act rates, or mandatory pension if no Social Security deduction.

While the use of the standardized tax amount may be appealing in its relative simplicity, it is unlikely in most cases to reflect the actual net income of a party who has any itemized deductions or any complexity to their income and tax status. For those cases, most practitioners will want to utilize and advocate for the individualized tax amount to be applied to determine net income. Using the individualized tax amount to determine net income requires the use of the properly calculated state and federal taxes. In fact, failure to use the individualized tax amount may fall well short of both the amount of child support which could have been ordered and our professional obligations to our clients. This is easy to avoid by using any of the child support calculation software programs available such as Family Law Software, which properly calculate the taxes based upon input of the correct data.

- Check for adjustments to gross or net income permitted by the statute. There are three main adjustments:

- Support for non-shared child. If a parent is paying court ordered support or actually paying financial support not ordered by a court, for a child not of the relationship (marriage or never-married partners or former partners) that support is a permitted adjustment from gross income. Court ordered support is completely deducted. Financial support paid not by court order is permitted at the amount actually paid or 75% of the amount that would be ordered under the guidelines, whichever is less. This will become a good reason to go in and get a court order for the other non-shared children. Keep in mind, that this adjustment should be done after, not before, the tax computation, since child support is not tax deductible!

- Maintenance paid or payable in the same proceeding to the same parent to whom child support would be payable. In addition, maintenance payments to a prior spouse is expected to be an adjustment added in the trailer bill. Note that maintenance paid to a prior spouse is not going to be an adjustment to income for that payor under this statute as currently enacted. The maintenance adjustment should be done from the gross income before determining the tax amounts, since maintenance is tax deductible and includible.

- Business income is fairly well defined in the new statute. The court now has the specific authority to reject accelerated depreciation, excessive or inappropriate business deductions and/or personal expenses paid through the business.

- Determine the combined net incomes of the two parents. This involves math, however simple this calculation may be. We generally hate math, so be prepared to pull out a calculator or the software referred to above. You will then refer to the Schedule (to be prepared by the Department) to find the appropriate level of child support obligation, based on that combined adjusted net income level and the number of children. This number is referred to in the statute as the ‘Basic Child Support Obligation’ (I am coining the acronym “BCSO”).

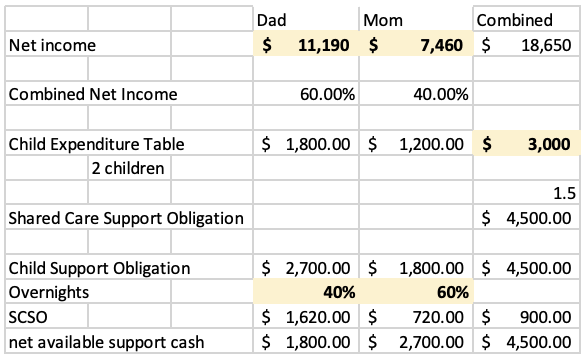

- This BCSO will then be allocated between the parties in the percentage of their respective net incomes to the combined adjusted net income. Assume the BCSO amount is $3,000 per month for two children, and Dad earns 60% of the income, and Mom 40%, then Dad’s share of the BCSO would be $1,800, and Mom’s would be $1,200. Assume Mom is the majority parenting time parent, with more than 60% of the overnights. This would result in a payment from Dad to Mom of $1,800. Mom’s $1,200 share remains with her, and is presumed to be used for the benefit of the child. Since we don’t yet have the Schedule, it is too soon to figure out if a BCSO would be less or more than the current percentage guidelines would require. If you want a preview, and have Family Law Software, take an existing case and look at the 2017 Child Support worksheet and see how the child support results change.

- Shared parenting time requires another two steps to the calculation. If both parents have at least 146 overnights, then the BCSO changes to a ‘shared care child support obligation’ (SCSO). This calculation requires first multiplying the BCSO by 1.5. The purpose of this increase from the BCSO to the SCSO is to account for the increase in costs for both parents providing shelter, food and other basic support to the child(ren) in their respective homes. The concept is that if there are least 146 overnights, the accommodations for the child(ren) will require greater costs than if the child(ren) are only there less than that. For your reference, 146 overnights translate to 40% of the overnights (146/365=.40), which is approximately equivalent to 6 out of 14 overnights in a regular two week parenting time schedule. Many other states have this type of enhancement of the BCSO to reflect allocation of parenting time, and use a 1.5 multiplier. Under the previous example, the $3,000 BCSO becomes a $4,500 SCSO. The original allocation of the BCSO between the parents based on their respective incomes is again applied to the SCSO. In our example, the 60/40 allocation is applied to the $4,500 SCSO. Dad is allocated $2,700, and Mom is allocated $1,800 of that $4,500 SCSO.

- Now comes the tricky part. Those allocated amounts are then cross multiplied by the allocation of parenting time to the other parent. If Dad has 40% of the parenting time, and Mom 60%, the calculation multiplies Dad’s $2,700 SCSO by .60 (the other parent’s parenting time allocation) to yield $1,620. Mom’s SCSO of $1,800 is multiplied by Dad’s share of the parenting time, 40%, to yield $720. Distinct from the BCSO, the SCSO is netted between the parties. Netting Dad’s obligation ($1,620) from Mom’s ($720) results in a payment of a support obligation from Dad to Mom of $900. After the payment from Dad to Mom, the shared child support obligation results in Mom having a total of $2,700 in her pocket to support the children, her own $1,800 portion of the SCSO plus Dad’s payment of $900. Dad has $1,800 in his pocket to support the children, his own $2,700 portion of the SCSO minus the $900 he pays to Mom. This reflects the shared income and allocation of parenting time for both parents. Example calculations using this scenario (wholly fictional) are below:

The allocation of responsibility for the support of the children is now expressly a shared obligation of both parents. Under the current ‘percentage of payor’s income’ model of computing child support obligations, the residential parent’s share of the support obligation was always part of the equation, but not expressly described or quantified. By including the residential parent’s share of the support obligation as part of the calculation and part of the result, it is hoped that the other parent will be more comfortable with the concept of payment of child support to that parent, resulting in less litigation and resistance to payment of support. In addition, it is hoped that the inclusion of parental time allocation in the equation will lessen the resistance to support payment. By including the parenting time allocation factor at 40% of the overnights, it is anticipated the knee-jerk demand for 50% of the time will be reduced and parenting time allocations will increasingly be based on the children’s needs and not the impact on support. Note in our example, Dad’s support payment to Mom went from $1,800 to $900 when he increased parenting time to 40% of the overnights.